The Supreme Court’s recent decision to accept the Union government’s 100-metre definition of the Aravalli hills has raised serious questions, especially because the court’s own expert panel had opposed the move.

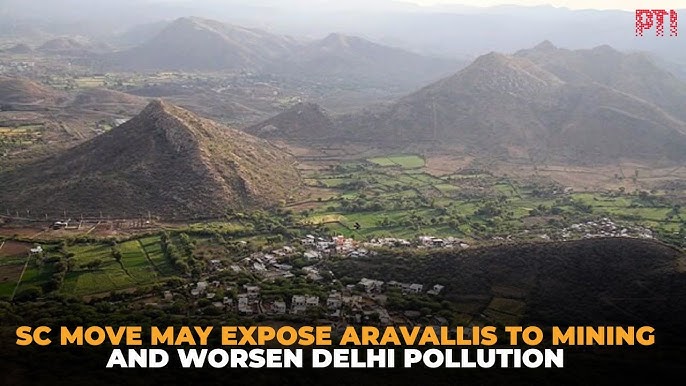

The Aravalli range, one of the oldest mountain systems in the world, plays a crucial role in blocking desertification, recharging groundwater, and maintaining ecological balance in north-western India. Any change in how these hills are defined directly affects mining, construction, and environmental protection.

What Is the 100-Metre Aravalli Rule?

On October 13, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) proposed a new definition of the Aravallis to the Supreme Court. According to this proposal, only land rising 100 metres or more above the surrounding area would be officially considered part of the Aravalli hills.

Just over a month later, on November 20, the Supreme Court accepted this definition.

Why Is This Decision Controversial?

The controversy arises because the Supreme Court’s Central Empowered Committee (CEC) — a body created by the court in 2002 to monitor forest and environmental matters — did not support the 100-metre definition.

In fact, the very next day after the government submitted its proposal, the CEC wrote to the court’s amicus curiae stating clearly that:

The CEC had not examined the proposal

The CEC had not approved the 100-metre definition

Despite this, the court went ahead and accepted the government’s recommendation.

What Definition Did the CEC Support?

The CEC strongly backed the definition prepared by the Forest Survey of India (FSI).

Under the FSI method:

Any land above the minimum elevation

With a slope of at least 3 degrees

is considered part of the Aravalli range.

Using this scientific method, the FSI mapped 40,481 square kilometres of Aravalli hills across 15 districts of Rajasthan. This approach ensures that even smaller and lower hills are protected, not just tall peaks.

Importantly, the FSI carried out this mapping under a Supreme Court order in 2010, after being asked to do so by the CEC itself.

Why the FSI Definition Matters

Environmental experts say the strength of the Aravalli range lies not only in its height but in its continuity.

he amicus curiae, K Parmeshwar, submitted a detailed presentation to the court highlighting serious problems with the 100-metre rule. According to him:

The new definition breaks the natural continuity of the Aravalli range

Many small hillocks, which are essential for ecology, will be excluded

These excluded areas could be opened up for mining

He warned that ignoring these smaller hills could lead to severe ecological damage, including the eastward spread of the Thar Desert.

Confusion Inside the Government Committee

In May 2024, the Supreme Court had directed the environment ministry to form a committee to develop a uniform definition of the Aravallis. A CEC representative, Dr JR Bhatt, was part of this committee.

However, the CEC later clarified that:

It was never shown the draft report

It never approved the ministry’s submission to the court

The CEC chairman wrote that the views attributed to the committee in the ministry’s affidavit were actually personal views, not the official position of the CEC. Adding to the confusion, the report submitted by the ministry was unsigned.

How Much of the Aravallis Could Lose Protection?

An internal assessment by the FSI, quoted later in the media, indicated that:

Over 91% of hills higher than 20 metres would be excluded under the 100-metre rule

If all Aravalli hills are counted, more than 99% would fall outside protection

Although the FSI later clarified that this was not a formal study, the figures highlight the scale of potential exclusion.

Government’s Stand on Mining

Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav stated that mining currently takes place in only 0.19% of the Aravalli region, about 278 square kilometres.

However, official data shows that this figure refers to existing mining areas, not what could happen in the future once large parts of the Aravallis are removed from protection.

The ministry has also admitted that the actual area covered under the 100-metre definition will only be known after ground surveys, raising questions about how assurances were given to the Supreme Court beforehand.

Why This Matters Beyond Mining

Experts warn that redefining the Aravallis is not just about mining permissions. The hills act as:

A natural barrier against desert expansion

A climate regulator

A groundwater recharge system

Weakening their legal protection could have long-term consequences for water security, air quality, and climate resilience in Rajasthan, Haryana, Delhi, and Gujarat.

The Bigger Question

The key concern remains unanswered:

Why did the Supreme Court accept a definition that its own expert committee and scientific data questioned?

As protests grow in Rajasthan and environmentalists raise alarms, the 100-metre Aravalli rule may continue to face legal, ecological, and public scrutiny in the days ahead.